On dog food, the (original) Metaverse, and (not) being bored¶

Introduction¶

Quote

Cutler, armed with a schedule, was urging the team to "eat its own dog food". Part macho stunt and part common sense, the "dog food diet" was the cornerstone of Cutler’s philosophy.

G. Pascal Zachary — Show-Stopper!

I can't remember exactly when it was -- it was likely late in 1994 or some time in 1995 -- when I first came across the concept of, or rather the name for the concept of, "eating your own dog food". The idea and the name played a huge part in the book Show-Stopper! by G. Pascal Zachary. The idea wasn't new to me of course; I'd been writing code for over a decade by then and plenty of times I'd built things and then used those things to do things, but it was fascinating to a mostly-self-taught 20-something me to be reading this (excellent -- go read it if you care about the history of your craft) book and to see the idea written down and named.

While Textualize isn't (thankfully -- really, I do recommend reading the book) anything like working on the team building Windows NT, the idea of taking a little time out from working on Textual, and instead work with Textual, makes a lot of sense. It's far too easy to get focused on adding things and improving things and tweaking things while losing sight of the fact that people will want to build with your product.

So you can imagine how pleased I was when Will announced that he wanted all of us to spend a couple or so weeks building something with Textual. I had, of course, already written one small application with the library, and had plans for another (in part it's how I ended up working here), but I'd yet to really dive in and try and build something more involved.

Giving it some thought: I wasn't entirely sure what I wanted to build though. I do want to use Textual to build a brand new terminal-based Norton Guide reader (not my first, not by a long way) but I felt that was possibly a bit too niche, and actually could take a bit too long anyway. Maybe not, it remains to be seen.

Eventually I decided on this approach: try and do a quick prototype of some daft idea each day or each couple of days, do that for a week or so, and then finally try and settle down on something less trivial. This approach should work well in that it'll help introduce me to more of Textual, help try out a few different parts of the library, and also hopefully discover some real pain-points with working with it and highlight a list of issues we should address -- as seen from the perspective of a developer working with the library.

So, here I am, at the end of week one. What I want to try and do is briefly (yes yes, I know, this introduction is the antithesis of brief) talk about what I built and perhaps try and highlight some lessons learnt, highlight some patterns I think are useful, and generally do an end-of-week version of a TIL. TWIL?

Yeah. I guess this is a TWIL.

gridinfo¶

I started the week by digging out a quick hack I'd done a couple of weeks

earlier, with a view to cleaning it up. It started out as a fun attempt to

do something with Rich Pixels

while also making a terminal-based take on

slstats.el. I'm actually pleased

with the result and how quickly it came together.

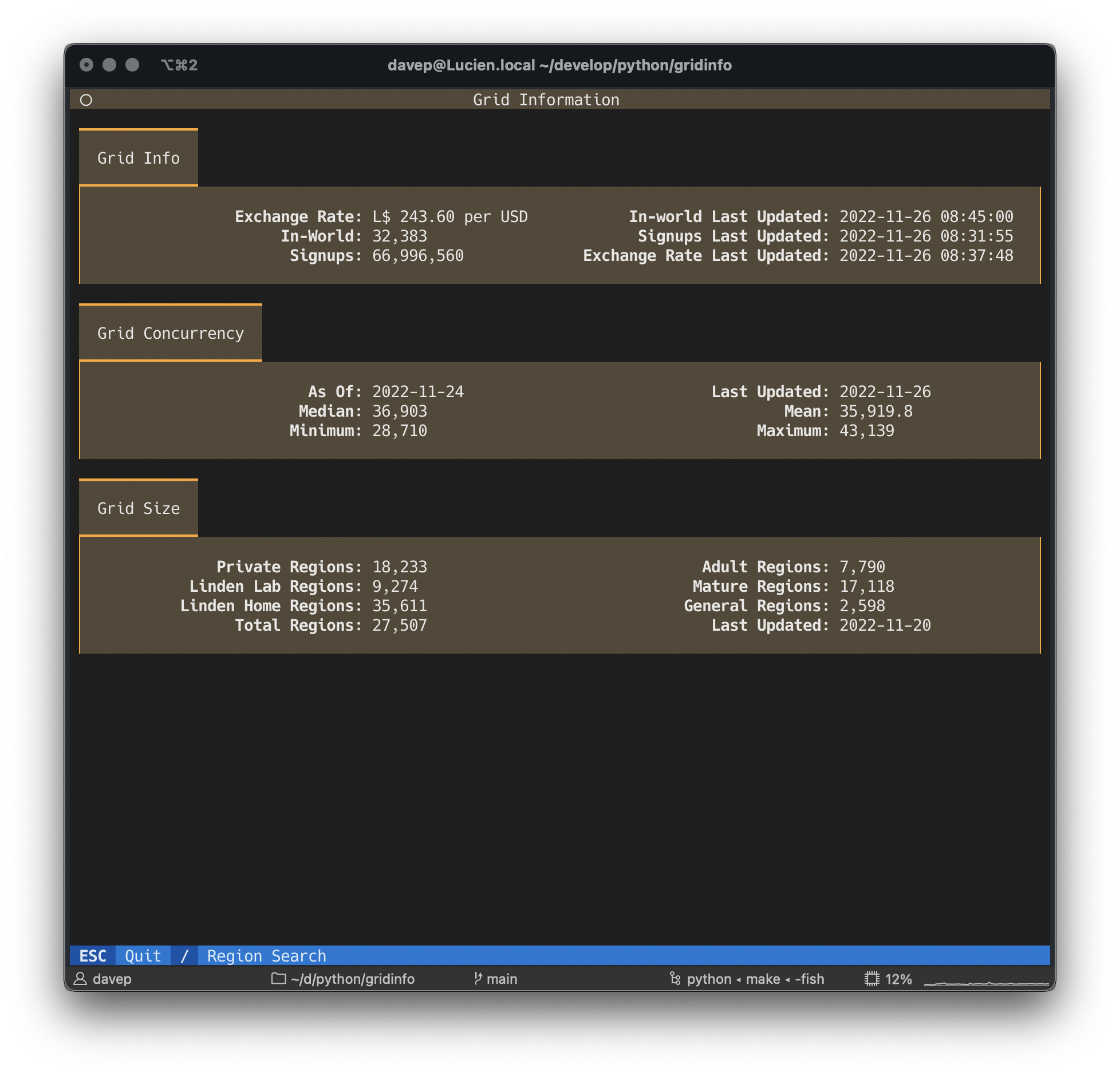

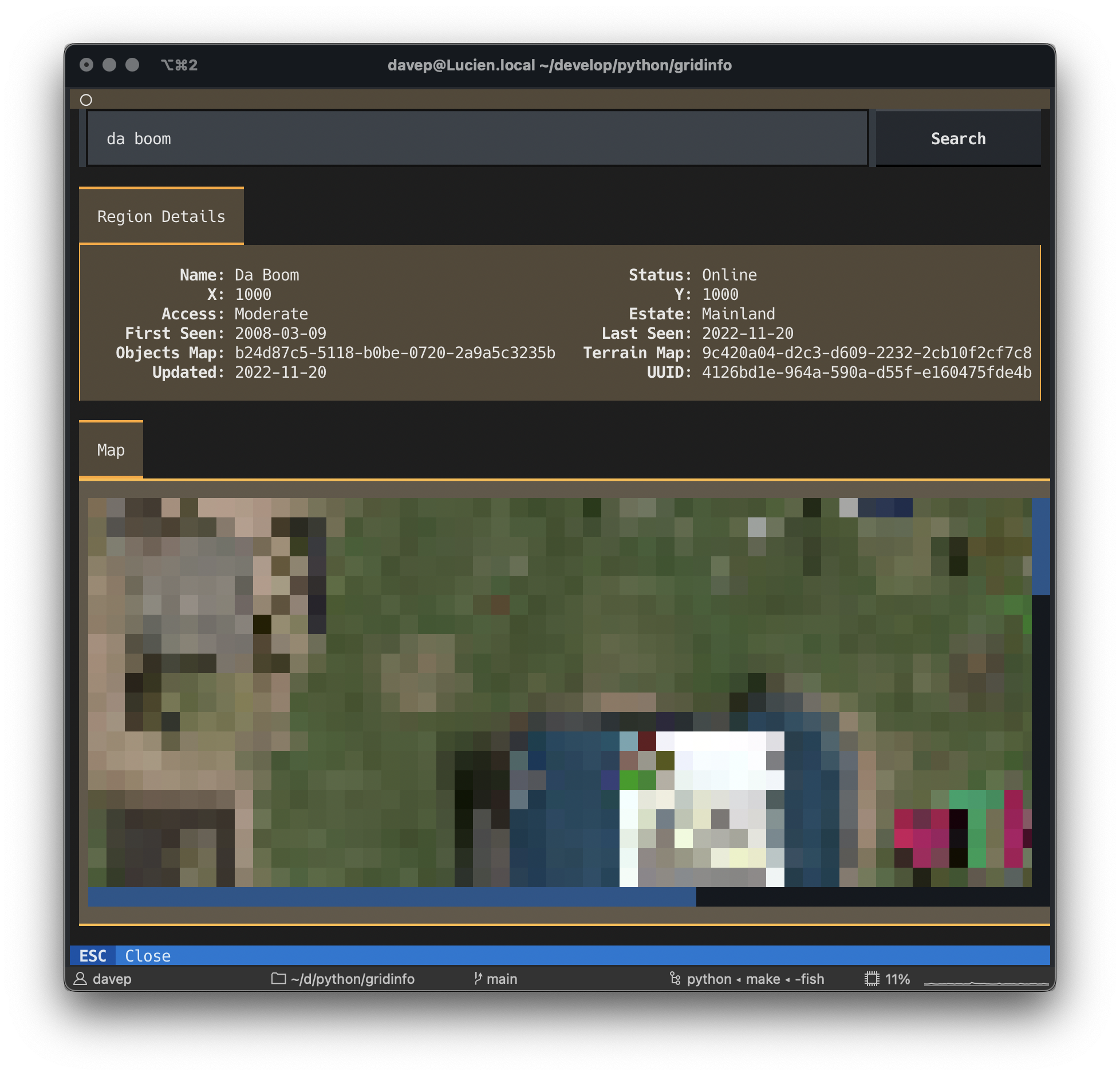

The point of the application itself is to show some general information about the current state of the Second Life grid (hello to any fellow residents of the original Metaverse!), and to also provide a simple region lookup screen that, using Rich Pixels, will display the object map (albeit in pretty low resolution -- but that's the fun of this!).

So the opening screen looks like this:

and a lookup of a region looks like this:

Here's a wee video of the whole thing in action:

Worth a highlight¶

Here's a couple of things from the code that I think are worth a highlight, as things to consider when building Textual apps:

Don't use the default screen¶

Use of the default Screen that's provided by the App is handy enough,

but I feel any non-trivial application should really put as much code as

possible in screens that relate to key "work". Here's the entirety of my

application code:

class GridInfo( App[ None ] ):

"""TUI app for showing information about the Second Life grid."""

CSS_PATH = "gridinfo.css"

"""The name of the CSS file for the app."""

TITLE = "Grid Information"

"""str: The title of the application."""

SCREENS = {

"main": Main,

"region": RegionInfo

}

"""The collection of application screens."""

def on_mount( self ) -> None:

"""Set up the application on startup."""

self.push_screen( "main" )

You'll notice there's no work done in the app, other than to declare the

screens, and to set the main screen running when the app is mounted.

Don't work hard on_mount¶

My initial version of the application had it loading up the data from the

Second Life and GridSurvey APIs in Main.on_mount. This obviously wasn't a

great idea as it made the startup appear slow. That's when I realised just

how handy

call_after_refresh

is. This meant I could show some placeholder information and then fire off

the requests (3 of them: one to get the main grid information, one to get

the grid concurrency data, and one to get the grid size data), keeping the

application looking active and updating the display when the replies came

in.

Pain points¶

While building this app I think there was only really the one pain-point,

and I suspect it's mostly more on me than on Textual itself: getting a good

layout and playing whack-a-mole with CSS. I suspect this is going to be down

to getting more and more familiar with CSS and the terminal (which is

different from laying things out for the web), while also practising with

various layout schemes -- which is where the revamped Placeholder

class

is going to be really useful.

unbored¶

The next application was initially going to be a very quick hack, but actually turned into a less-trivial build than I'd initially envisaged; not in a negative way though. The more I played with it the more I explored and I feel that this ended up being my first really good exploration of some useful (personal -- your kilometerage may vary) patterns and approaches when working with Textual.

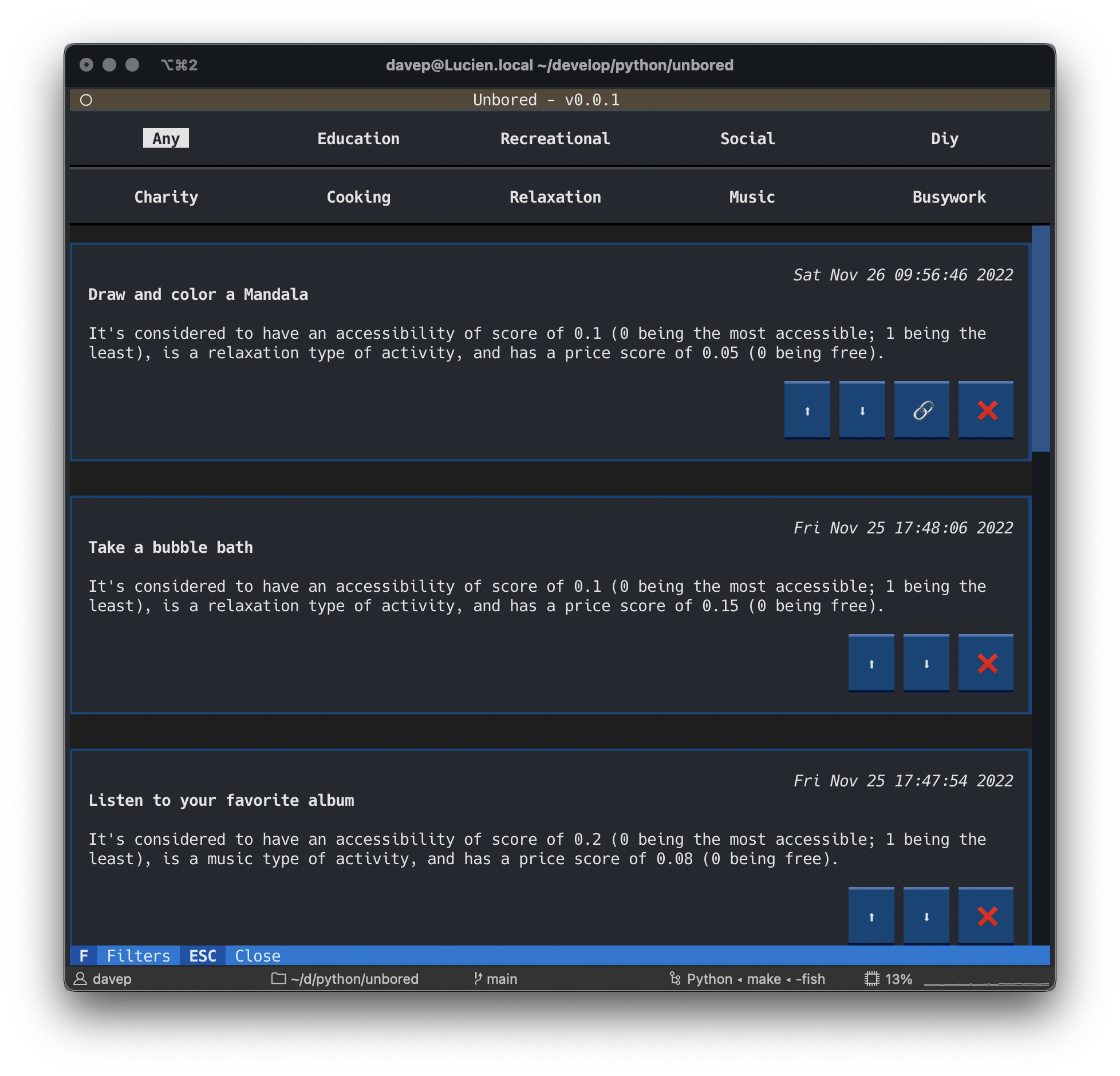

The application itself is a terminal client for the Bored-API. I had initially intended to roll my own code for working with the API, but I noticed that someone had done a nice library for it and it seemed silly to not build on that. Not needing to faff with that, I could concentrate on the application itself.

At first I was just going to let the user click away at a button that showed a random activity, but this quickly morphed into a "why don't I make this into a sort of TODO list builder app, where you can add things to do when you are bored, and delete things you don't care for or have done" approach.

Here's a view of the main screen:

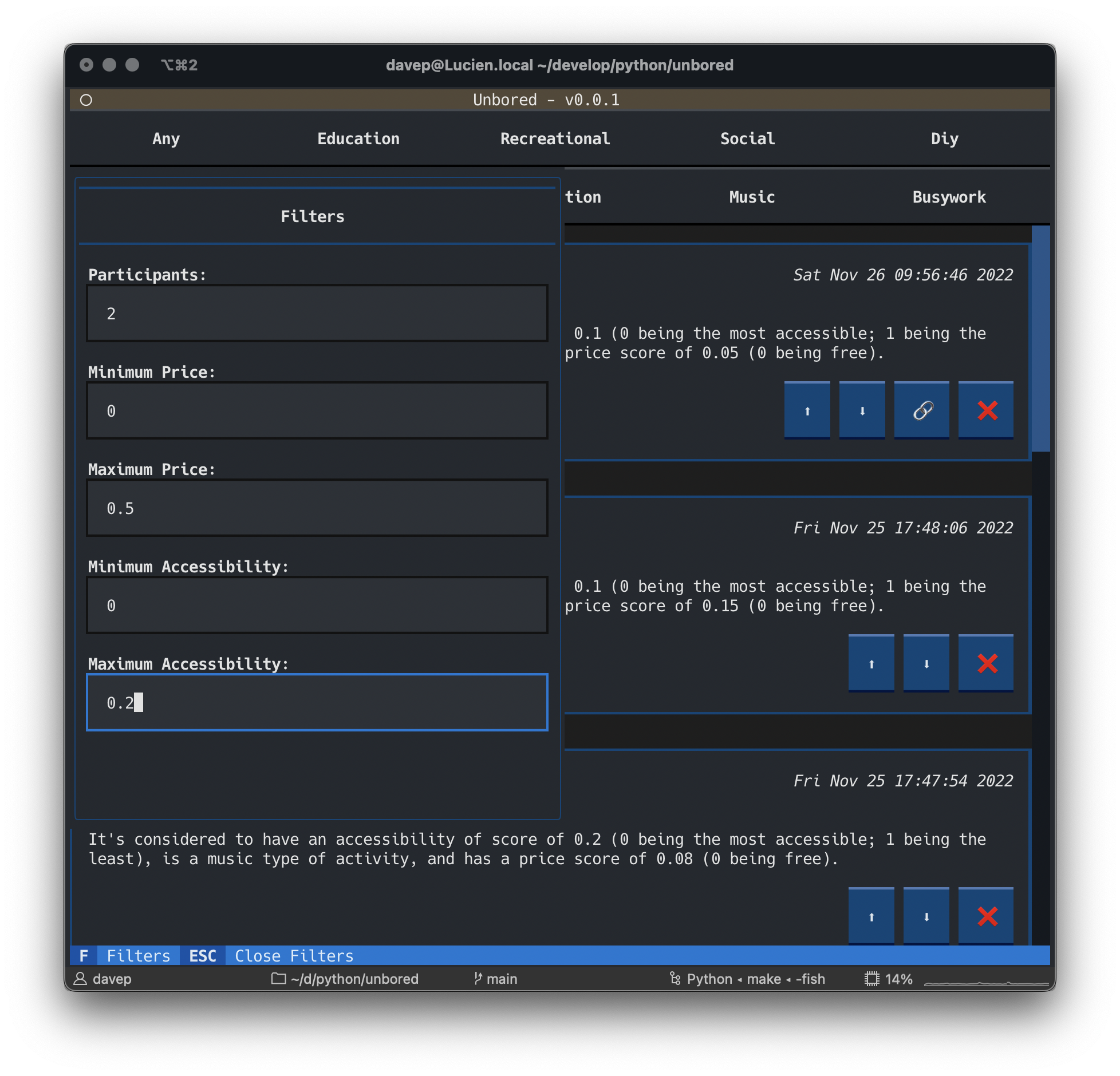

and here's a view of the filter pop-over:

Worth a highlight¶

Don't put all your BINDINGS in one place¶

This came about from me overloading the use of the escape key. I wanted it

to work more or less like this:

- If you're inside an activity, move focus up to the activity type selection buttons.

- If the filter pop-over is visible, close that.

- Otherwise exit the application.

It was easy enough to do, and I had an action in the Main screen that

escape was bound to (again, in the Main screen) that did all this logic

with some if/elif work but it didn't feel elegant. Moreover, it meant

that the Footer always displayed the same description for the key.

That's when I realised that it made way more sense to have a Binding for

escape in every widget that was the actual context for escape's use. So I

went from one top-level binding to...

...

class Activity( Widget ):

"""A widget that holds and displays a suggested activity."""

BINDINGS = [

...

Binding( "escape", "deselect", "Switch to Types" )

]

...

class Filters( Vertical ):

"""Filtering sidebar."""

BINDINGS = [

Binding( "escape", "close", "Close Filters" )

]

...

class Main( Screen ):

"""The main application screen."""

BINDINGS = [

Binding( "escape", "quit", "Close" )

]

"""The bindings for the main screen."""

This was so much cleaner and I got better Footer descriptions too. I'm

going to be leaning hard on this approach from now on.

Messages are awesome¶

Until I wrote this application I hadn't really had a need to define or use

my own Messages. During work on this I realised how handy they really are.

In the code I have an Activity widget which takes care of the job of

moving itself amongst its siblings if the user asks to move an activity up

or down. When this happens I also want the Main screen to save the

activities to the filesystem as things have changed.

Thing is: I don't want the screen to know what an Activity is capable of

and I don't want an Activity to know what the screen is capable of;

especially the latter as I really don't want a child of a screen to know

what the screen can do (in this case "save stuff").

This is where messages come in. Using a message I could just set things up

so that the Activity could shout out "HEY I JUST DID A THING THAT CHANGES

ME" and not care who is listening and not care what they do with that

information.

So, thanks to this bit of code in my Activity widget...

class Moved( Message ):

"""A message to indicate that an activity has moved."""

def action_move_up( self ) -> None:

"""Move this activity up one place in the list."""

if self.parent is not None and not self.is_first:

parent = cast( Widget, self.parent )

parent.move_child(

self, before=parent.children.index( self ) - 1

)

self.emit_no_wait( self.Moved( self ) )

self.scroll_visible( top=True )

...the Main screen can do this:

def on_activity_moved( self, _: Activity.Moved ) -> None:

"""React to an activity being moved."""

self.save_activity_list()

Warning

The code above used emit_no_wait. Since this blog post was first

published that method has been removed from Textual. You should use

post_message_no_wait or post_message instead now.

Pain points¶

On top of the issues of getting to know terminal-based-CSS that I mentioned earlier:

- Textual currently lacks any sort of selection list or radio-set widget. This meant that I couldn't quite do the activity type picking how I would have wanted. Of course I could have rolled my own widgets for this, but I think I'd sooner wait until such things are in Textual itself.

- Similar to that, I could have used some validating

Inputwidgets. They too are on the roadmap but I managed to cobble together fairly good working versions for my purposes. In doing so though I did further highlight that the reactive attribute facility needs a wee bit more attention as I ran into some (already-known) bugs. Thankfully in my case it was a very easy workaround. - Scrolling in general seems a wee bit off when it comes to widgets that are more than one line tall. While there's nothing really obvious I can point my finger at, I'm finding that scrolling containers sometimes get confused about what should be in view. This becomes very obvious when forcing things to scroll from code. I feel this deserves a dedicated test application to explore this more.

Conclusion¶

The first week of "dogfooding" has been fun and I'm more convinced than

ever that it's an excellent exercise for Textualize to engage in. I didn't

quite manage my plan of "one silly trivial prototype per day", which means

I've ended up with two (well technically one and a half I guess given that

gridinfo already existed as a prototype) applications rather than four.

I'm okay with that. I got a lot of utility out of this.

Now to look at the list of ideas I have going and think about what I'll kick next week off with...