Smoother scrolling in the terminal — a feature decades in the making

The great philosopher F. Bueller once said “Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”

Beuller was not taking about terminals, which tend not to move very fast at all. Until they do. From time to time terminals acquire new abilities after a long plateau. We are now seeing a kind of punctuated evolution in terminals which makes things possible that just weren't feasible a short time ago.

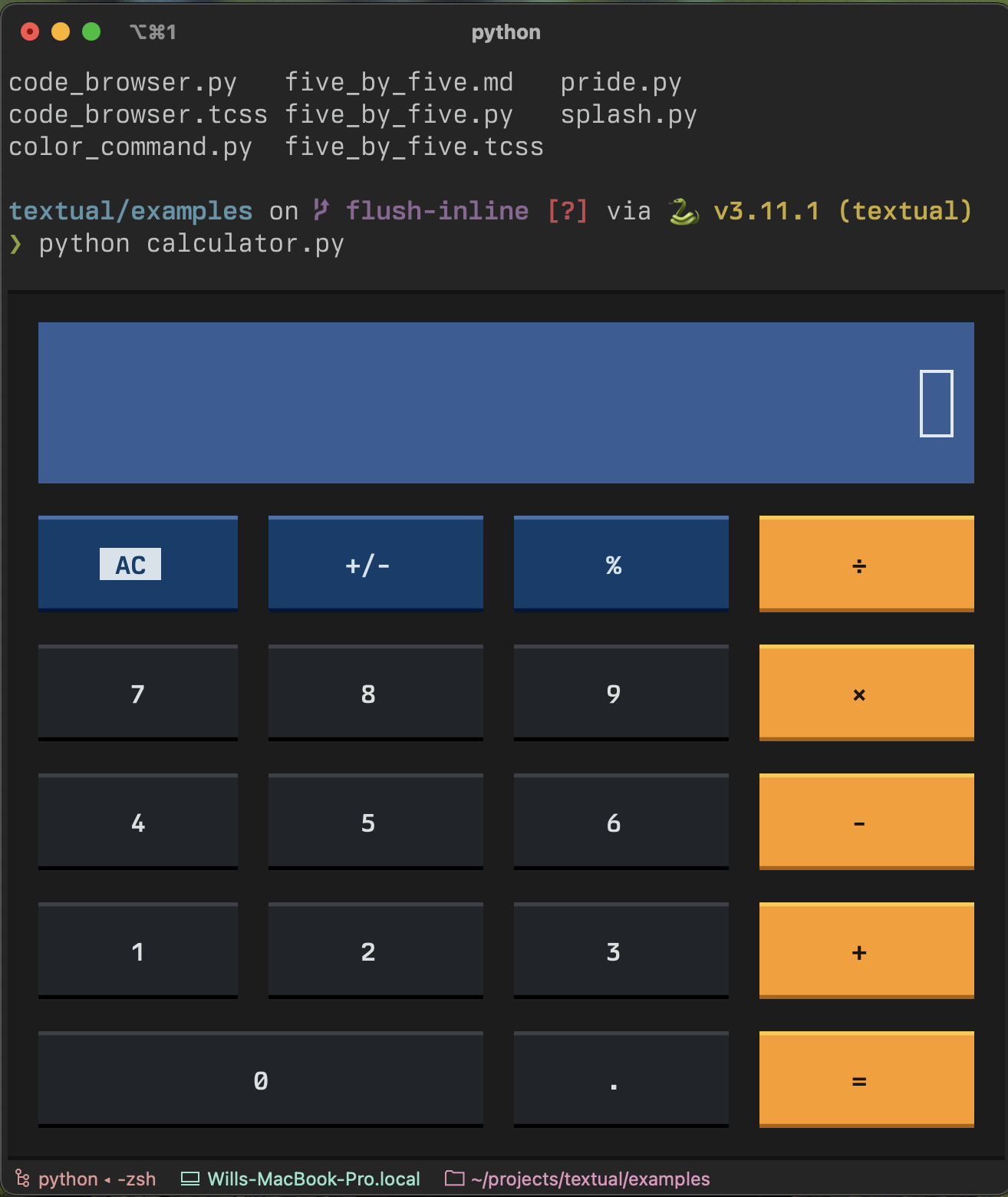

I want to talk about one such feature, which I believe has been decades1 in the making. Take a look at the following screen recording (taken from a TUI running in the terminal):